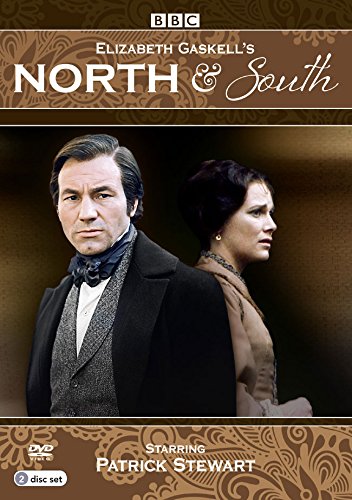

I recently re-watched an old favourite of mine, North and South, starring Richard Armitage and Daniela Denby-Ashe. This BBC period drama was not widely publicised when it first aired in 2004, as it was not believed that it would be very popular. Since then, it has appeared on most recommended lists for period dramas and has become a firm favourite – a must-see for every self-respecting fan of romantic historical fiction.

But more about that later. What I wanted to write about today is to do with a shock discovery I made when, eager not to let the magic of that final ‘train station kiss’ scene fade, I began searching the internet to see what others made of this drama. And then I saw it – a bit of trivia on the IMDB website: Tim Pigott Smith (who plays Mr. Hale) also plays Frederick Hale in the 1975 version. Version of what? I asked myself. Surely not a version of North and South. Surely I would know about this. I searched a little more and there it was: a BBC 1975 mini-series of Elizabeth Gaskell’s romantic and gritty novel. It exists, and not only that, but in my opinion, it’s pretty good.

I pride myself on my knowledge of 1970s costume drama; it’s something of which I’m very fond. I don’t know quite what it is – perhaps the nostalgic memories of watching The Onedin Line at my grandma’s house when I was little, or perhaps it’s the safety of them – you know there’ll be no in-your-face nudity or graphic violence. So, I suppose I was already disposed to like this drama, were it not for the fact that, as I already mentioned, the 2004 version is a favourite. How could it be improved upon?

Well, in many ways, this new discovery of mine was more faithful to the novel, or what I can remember of it, particularly with regards to the characters of Nicholas and Bessy Higgins. This Bessy is much more your typical tragic Victorian sub-character, designed to pull at the heart strings of well-to-do Victorians, who might be inspired to consider and sympathise with the plight of the working classes more.

Well, in many ways, this new discovery of mine was more faithful to the novel, or what I can remember of it, particularly with regards to the characters of Nicholas and Bessy Higgins. This Bessy is much more your typical tragic Victorian sub-character, designed to pull at the heart strings of well-to-do Victorians, who might be inspired to consider and sympathise with the plight of the working classes more.

The storyline generally follows that of the novel, although it does miss out the rather important plot point in which Frederick pushes Leonards, who later dies, and Margaret has to deny that she was present. I read North and South several years ago, so I cannot remember exactly how it all plays out, but it seems to me that this is a pretty important and catalytic detail to have missed out. In the 2004 version at least, this is when Margaret has to ask herself the question: Why would Mr. Thornton go along with my story when he knows that I am lying about being at the station? It’s perhaps when she realises that there really is something deep and unconditional about the love he has declared for her.

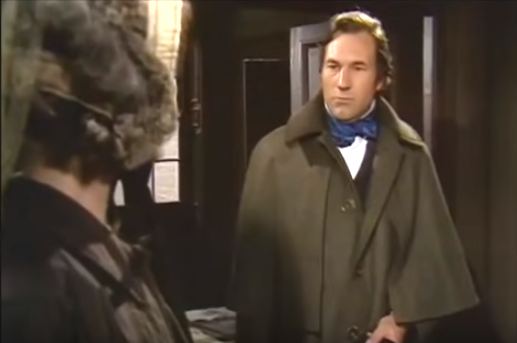

This version finds other ways to reveal Thorton’s love for Margaret which are more upfront and, I felt, sweet. Patrick Stewart’s Mr. Thornton is similar to the one in the novel. It could come as a shock to fans who have not read it that Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mr. Thornton is generally friendly and cheerful and wears his heart on his sleeve. It’s a much more ordinary man who first meets with Margaret Hale in this version; not as he beats one of his workers up for smoking in the factory, but as a matter of courtesy when he decides it would be kind to pay a house visit to the new tenants. It’s important to state here that I love a dark and brooding hero, but something about Stewart’s performance is very endearing in this adaptation, so that, even without the heart wrenching ‘Look back at me’ scene of 2004, I was still longing for Margaret to put the man out of his misery and reciprocate his love.

Towards the end of this version, Margaret’s regret over her rejection of Mr. Thornton and her realisation that she does love him after all, is referenced more often and more obviously. I liked Rosalind Shanks’ Margaret Hale, even though she seems to smile once or twice in the first scene and then never again. She plays her much more as a product of her times; a heroine that really would have appealed to a Victorian readership, and one can see why Stewart’s rather less sophisticated Mr. Thornton might be awe-struck by the appearance of this refined and beautiful lady from the south.

To conclude then, I honestly can’t say which version I prefer, as I feel that both have something different to offer. In the 1975 version, I felt I got much more of a sense of Margaret Hale’s back story and Thornton’s humanity. Maybe I just need things spelled out a little more, but I’d never made the connection between his sudden concern for Boucher’s children after Higgins asks him for work, and his own experience of losing a parent to suicide. This, and many other points make the 1975 version one that I feel I learnt more from, and I really did like the portrayal of the main characters. But that train scene between Armitage and Denby-Ashe…It’s got to be a draw.